The Regent Kings of Thondaimandalam

Art, Architecture, Endowments, and Other Contributions

The Pallava Kings

The Pallava Kings settled in Kanchipuram in the 6th century. Under the Pallavas, Kanchipuram flourished as a center of Hindu learning and was known as the ghatikasthanam, or “place of learning”. The Pallavas fortified the city with ramparts, wide moats, well-laid-out roads and artistic temples.

The Pallava King Mahendravarman II (600-630 A.D.) was the most remarkable of the Pallavas monarch. He introduced the cave style of architecture. Named Ardent Jaina in his earlier life, he later embraced Adi Shaiva influenced by the enlightened Shaiva saint Appar.

Narasimhavarman I, surnamed Mahamalla (630-660 A.D.), the son and successor of Mahendravarma I was an ardent lover of art and consecrated cave-temples at different places such as Trichinopoly and Pudukkotai. His name is, however, best known in connection with the stone Rathas (chariots made of stone) of Mahabalipuram. The original name of the place, Mahamallapura commemorates its royal founder, Mahamalla, i.e., Narasimhavarman I.

Pancha Rathas (Pancha – five; Rathas – chariots) in stone, sculpted at Mamallapuram in Thondaimandalam, during the reign of Narasimhavarman I

The Pallava King Narasimhavarman II (680-720 A.D.) also known as Rajasimha built important Hindu temples. To name a few: the Kailasanathar Temple, the Varadaraja Perumal Temple, the Iravatanesvara Temple – all three in Kanchipuram and the Shore temple at Mahabalipuram. The Varadharaja Perumal Temple covering 23 acres (93,000 m2), is the largest Vishnu temple in Kanchipuram. The temple features carved lizards, one plated with gold and another with silver. It is the oldest Vishnu temple in the city. During the reign of Rajasimha Narasimhavarman II the rock-cut technique was replaced by the structural temple of masonry and stone.

He is also said to have sent embassies to China, and maritime trade flourished during his reign.

The Pallava Kings settled in Kanchipuram in the 6th century. Under the Pallavas, Kanchipuram flourished as a center of Hindu learning and was known as the ghatikasthanam, or “place of learning”. The Pallavas fortified the city with ramparts, wide moats, well-laid-out roads and artistic temples.

The Pallava King Mahendravarman II (600-630 A.D.) was the most remarkable of the Pallavas monarch. He introduced the cave style of architecture. Named Ardent Jaina in his earlier life, he later embraced Adi Shaiva influenced by the enlightened Shaiva saint Appar.

Narasimhavarman I, surnamed Mahamalla (630-660 A.D.), the son and successor of Mahendravarma I was an ardent lover of art and consecrated cave-temples at different places such as Trichinopoly and Pudukkotai. His name is, however, best known in connection with the stone Rathas (chariots made of stone) of Mahabalipuram. The original name of the place, Mahamallapura commemorates its royal founder, Mahamalla, i.e., Narasimhavarman I.

Varadaraja Perumal Temple

Iravataneshwarar temple, Kanchipuram in Thondaimandalam

Shore temple in Mahabalipuram, Thondaimandalam

Kailasanatha Temple, Kanchipuram

A few other temples in Kanchipuram built by the regent Pallava Kings

- Muktheeswarar Temple built by Nandivarman Pallava II (720– 796)

- The Karchapeswarar Temple, Onakanthan Tali, Kachi Anekatangapadam, Kuranganilmuttam, and Karaithirunathar Temple in Tirukalimedu – Shiva temples in the city revered in Tevaram, the Tamil Adi Shaiva canonical work of the 7th–8th centuries.

- Kumarakottam Temple, dedicated to Lord Muruga

- Ashtabujakaram, Tiruvekkaa, Tiruththanka, Tiruvelukkai, Ulagalantha Perumal Temple, Tiru Pavla vannam, Pandava Thoothar Perumal Temple are among the divyadesam, the 108 famous temples of Vishnu in the city.

The development of temple architecture, particularly Dravida style, not only set the standard in the South Indian peninsula, but also largely influenced the architecture of the Indian colonies in the Far East. The characteristic Pallava or Dravidian type of Sikhara is met within the temples of Java, Cambodia and Vietnam.

Literature and Religion:

Sanskrit which is the Deva bhasha – God’s own language – was the official language of the Pallavas and Kanchipuram. The Pallava capital was a great centre of Sanskrit learning. Both Bharavi and Dandin, the authors of Kiratarjuniyam and Dasakumarcharitam respectively, lived in the Pallava court. Dandin was also the author of the text “Avanti Sundari Kathasara”. Pallavas were orthodox Brahmanical Hindus and their patronage was responsible for the great reformation of the medieval ages.

It was the British rule that strategised and destroyed this ancient learning system and deliberately replaced the enlightenment-based Sanskrit language with English and the ancient enlightenment-based education system with the Macaulay education system, thus destroying a vital component of the enlightenment ecosystem.

The Chola Kings

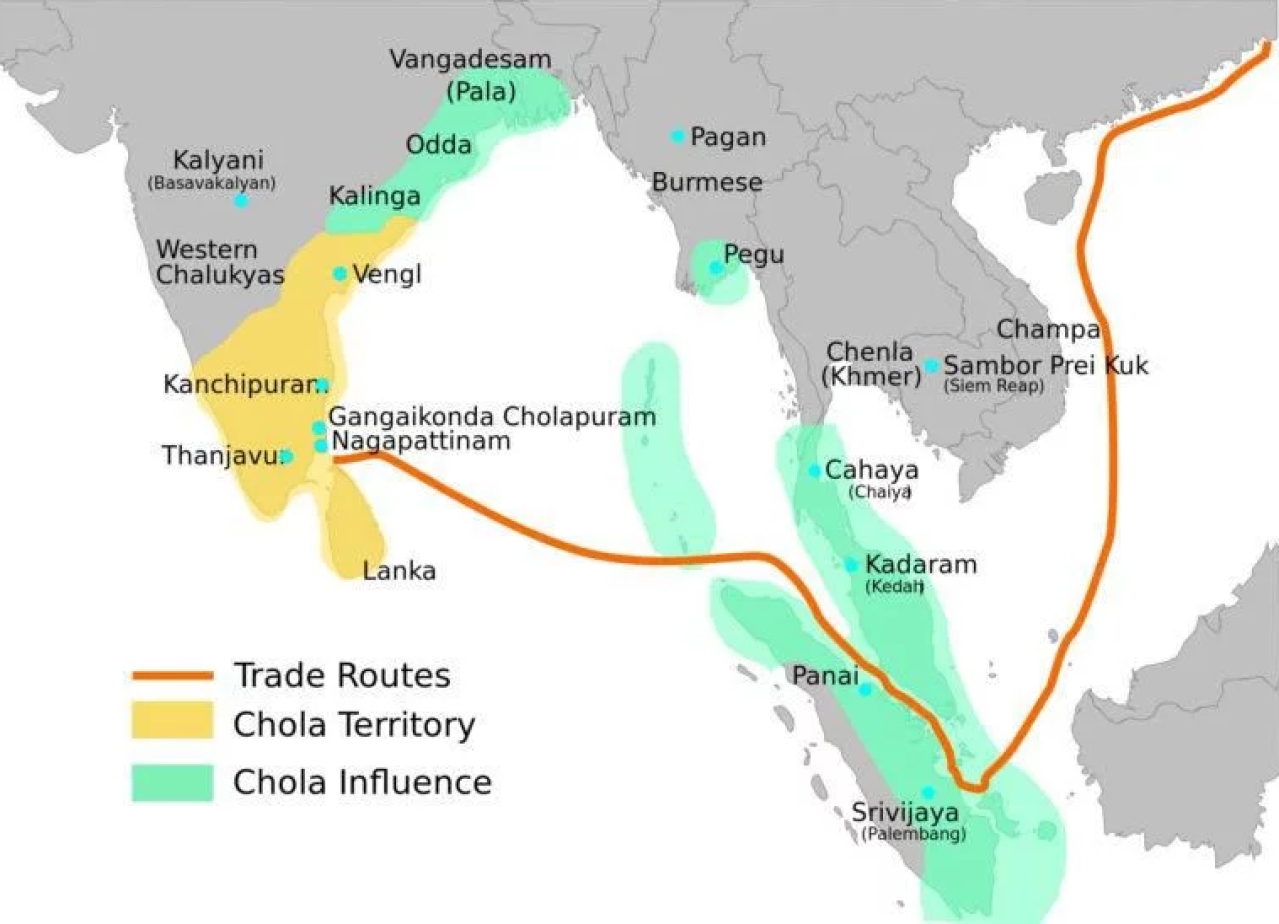

The Chola Dynasty extent

The Chola Dynasty ruled primarily in southern India until the thirteenth century. The dynasty originated in the fertile valley of the Kaveri River. Karikala Chola stands as the most famous among the early Chola kings, while Rajaraja Chola, Rajendra Chola and Kulothunga Chola I ruled as notable emperors of the medieval Cholas. The Cholas reached the height of their power during the tenth, eleventh and twelfth centuries.

Under Rajaraja Chola I and his son Rajendra Chola, the dynasty became a military, economic and cultural power in Asia. The Chola territories stretched from the islands of the Maldives in the South including Sri Lanka to as far North as the banks of the Godavari River in Andhra Pradesh. Historians during the past 150 years have gained a lot of knowledge on ancient history from a variety of sources such as ancient Tamil Sangam literature, oral traditions, religious texts, temple stone inscriptions and copper plate inscriptions.

A large number of stone inscriptions by the Cholas themselves and by their rival kings, Pandyas and Chalukyas, and copper-plate grants, have been instrumental in constructing the history of Cholas. Around 850 CE, King Vijayalaya established the imperial line of the medieval Cholas.

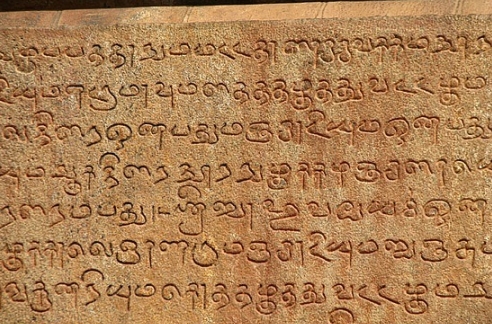

A stone inscription from the Chola period

Temple Building – A Major Activity

The Cholas continued the temple-building traditions of the Pallava dynasty and contributed significantly to the Dravidian temple design and endowed great wealth to them. The temples acted not only as places of worship but as centres of economic activity, benefiting the entire living community. They built numerous temples throughout their kingdom such as the Brihadeshvara Temple. Aditya I built a number of Siva temples along the banks of the river Kaveri. Those temples ranged from small to medium scale until the end of the tenth century.

Temple building received great impetus from the conquests and the genius of Rajaraja Chola and his son Rajendra Chola I (r. 1014 C.E.). The maturity and grandeur to which the Chola architecture had evolved found expression in the Brihadeeswara temple in Tanjavur.

Chola Bronzes become much sought after

The Chola dynasty’s remarkable sculptures and bronzes set their period apart. Among the existing specimens in museums around the world and in the temples of South India may be seen many fine figures of Siva in various forms, Vishnu and his consort Lakshmi, and the Siva saints carved.

Local government

Every village was made a self-governing unit. A number of villages constituted a larger entity known as a Kurram, Nadu, or Kottram, depending on the area. A number of kurrams constituted a valanadu. Those structures underwent constant change and refinement throughout the Chola period. Justice represented mostly a local matter in the Chola Empire with minor disputes settled at the village level. Punishment for minor crimes came in the form of fines or a direction for the offender to donate to some charitable endowment. Even crimes such as manslaughter or murder received fines as punishment. The king himself heard and decided crimes of the state, such as treason with the typical punishment either execution or the confiscation of property.

A prosperous and literate Chola society

The overwhelming stability in the core Chola region enabled the people to lead productive and contented lives. The quality of the inscriptions of the regime indicates a presence of high level of literacy and education in the society. Court poets wrote and talented artisans engraved the text in those inscriptions.

Education system

People considered education in the contemporary sense unimportant. Circumstantial evidence suggests that some village councils organized schools to teach the basics of reading and writing to children. Vocational education took the form of apprenticeship, with the father passing on his skills to his sons. Tamil served as the medium of education for the masses; the Brahmins alone had Sanskrit education. Religious monasteries (matha or gatika), supported by the government, emerged as centres of learning. This is what is known as Gurukul where the children learn with a Guru, the consciousness-based method.

Art, Architecture, Culture flourish – Influence on South East Asia & China

Under the Cholas, the Tamil country reached new heights of excellence in art, religion and literature. Monumental architecture in the form of majestic temples and sculpture in stone and bronze reached a finesse never before achieved in India. The Cholas excelled in maritime activity in both military and the mercantile fields. Their continued commercial contacts with the Chinese Empire, enabled them to influence the local cultures. Many of the surviving examples of the Hindu cultural influence are found today throughout the Southeast Asia owe much to the legacy of the Cholas.

Tamil Literature – Golden Age

The age of the Imperial Cholas (850–1200) represented the golden age of Tamil culture, marked by the importance of literature. Chola inscriptions cite many works, although tragically most of them have been lost. The great Tamil poet Kamban flourished during the reign of Kulothunga Chola III. His work Ramavatharam (depicting the life of Lord Rama) represents the greatest epic in Tamil Literature, and although the author states that he followed Sage Valmiki, his work transcends a mere translation or simple adaptation of the Sanskrit epic by Sage Valmiki.

The famous Tamil poet Ottakuttan lived as a contemporary of Kulothunga Chola I. He wrote Kulothunga Solan Ula a poem extolling the virtues of the Chola king. He served at the courts of three of the king’s successors. The impulse to produce devotional religious literature continued into the Chola period and the arrangement of the Saiva canon into eleven books represented the work of Nambi Andar Nambi, who lived close to the end of 10th century.

Nambiandar Nambi

The Vijayanagar Kings

The Vijaynagara Empire

The Vijayanagar empire, 1336–1646 founded in 1336 in the wake of the rebellions against the Mughal Tughluq rule in the Deccan, lasted for more than two centuries as the dominant power in south India. Its history and fortunes were shaped by the increasing militarization of peninsular politics after the Muslim invasions.

The Vijayanagar Kings redeemed Kanchipuram from the Mughal Kings and ruled Kanchipuram from 1361 to 1645. The earliest stone inscriptions attesting to the Vijayanagar rule are those of King Kumara Kampanna from 1364 and 1367, which were found in the precincts of the Kailasanathar Temple and Varadaraja Perumal Temple respectively. His inscriptions record the re-institution of Hindu rituals in the Kailasanathar Temple that were stopped during the Muslim invasions. King Harihara II endowed grants in favour of the Varadaraja Perumal Temple. King Narasimha of the Saluva dynasty donated generously to the Varadaraja Perumal Temple.

Kanchipuram was visited twice by the Vijayanagar king Krishna Deva Raya, considered to be the greatest of the Vijayanagar rulers, and 16 inscriptions of his time are found in the Varadaraja Perumal Temple. The inscriptions in four languages – Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, and Sanskrit – record the genealogy of the Tuluvakings and their contributions, along with those of their nobles, towards the upkeep of the shrine. His successor, Achyuta Deva Raya, reportedly had himself weighed against pearls in Kanchipuram and distributed the pearls amongst the poor. Such was the prosperity of the Thondaimandalam region until persecution.

Virupaksha temple

The kingdom of Vijayanagar was founded by Harihara and Bukka, two of five brothers (surnamed Sangama) who had served in the administrations of both Kakatiya and Kampili before those kingdoms were conquered by the armies of the Delhi sultanate (invaders) in the 1320s. When Kampili fell in 1327, the two brothers were captured and taken to Delhi, where they were converted to Islam. They were returned to the Deccan as governors of Kampili for the Sultanate rule with the hope that they would be able to deal with the many local revolts. The brothers reconverted to Hinduism under the influence of the great Hindu sage Madhavacarya (Vidyaranya) and proclaimed their independence from the Delhi sultanate.

During Harihara’s reign the administrative foundation of the Vijayanagar state was laid. King Harihara also encouraged increased cultivation in some areas by allowing lower revenue payments for lands recently reclaimed from the forests. King Harihara was succeeded by Bukka (reigned 1356–77), who during his first decade as king engaged in a number of costly wars against the Bahmanī Sultans over control of strategic forts in the Tungabhadra-Krishna Doab, as well as over the trading emporia of the east and west coasts. The Bahmanīs generally prevailed in these encounters and even forced Vijayanagar to pay a tribute in 1359. The major accomplishments of Bukka’s reign were the conquest of the short- lived sultanate of Maʿbar (Madurai; 1370) and the maintenance of his kingdom against the threat of decentralization. The Bahmanī sultan however besieged Vijayanagar in 1398–99, slaughtered a large number of people, and exacted a promise to pay tribute.

Under Vijayanagar rule, temples, which exhibited such singularly imperial features as huge enclosures and entrance gateways (gopuras), emerged as major political arenas. Monastic organizations (mathas) representing various religious traditions also became focal points of local authority, often closely linked with the Nayaka chieftaincies. A fairly elaborate and specialized administrative infrastructure underlay these diverse local and regional religio-political forms.

Vijayanagar the city was a symbol of vast power and wealth. It was a royal ceremonial and administrative centre and the nexus of trade routes. Foreign travelers and visitors were impressed by the variety and quality of commodities that reached the city, by the architectural grandeur of the palace complex and temples, and by the ceremonial significance of the annual Mahanavami celebrations, at which the Nayakas and other chiefs assembled to pay tribute.

Vijayanagar was, to some extent, consciously represented by its sovereigns as the last bastion of Hinduism against the forces of Islam. After the fall of the Vijayanagar Empire, Kanchipuram endured over two decades of persecution and political turmoil. The Golconda Sultanate gained control of the city in 1672, but lost it to Bijapur three years later. In 1676, Shivaji arrived in Kanchipuram at the invitation of the Golconda Sultanate in order to drive out the Bijapur forces. His campaign was successful and Kanchipuram was held by the Golconda Sultanate until its conquest by the Mughal Empire led by Aurangazeb in October 1687. In the course of their southern campaign, the Mughals defeated the Marathas under Sambhaji, the elder son of Shivaji, in a battle near Kanchipuram in 1688 which caused considerable damage to the city and further strengthened the Mughal rule.

Soon after, the priests at the Varadaraja Perumal, Ekambareshwarar and Kamakshi Amman temples, mindful of Aurangazeb’s reputation for iconoclasm, transported the deities to southern Tamil Nadu and did not restore them until after Aurangzeb’s death in 1707. Under the Mughals, Kanchipuram was part of the viceroyalty of the Carnatic which, in the early 1700s, began to function independently, retaining only a nominal acknowledgment of Mughal rule.

Other Rulers

The Hoysala Kings

Stone Inscriptions indicate the presence of a powerful Hoysala garrison in Kanchipuram, which remained in the city until about 1230. In 1311, Malik Kafur, sent by the Mughal King Alauddin Khilji invaded Kanchipuram. Due to the ruthless persecution, the sacred rituals in the temple were forced to be abandoned.

The Bahmanian Sultanate Invasion of Kancheepuram

The Bahmani Sultanate, or Bahmanid Empire occupied the North Deccan region to the river Krishna and inflicted ruthless Muslim invasion of southern India between 1347 and 1527. The Bahmani Sultanate was in constant war with the Hindu kings of the Vijayanagara Empire. The Sultanate wanted the fertile lands of India that lay between the two kingdoms called the Raichur Doab. Firuz Shah wanted to develop the Deccan region as India’s cultural hub. He waged three battles against the Vijaynagar Empire and extended his territories.

In the Bahmani Sultanate, Shamsuddin Muhammad succeeded his brother when he was 9 or 10 years old. Mahmud Gawan was made his Prime minister. Gawan helped the Bahmani State attain prosperity unequaled in its history by plundering and persecuting the Indian territory. The boundaries of the Bahmani Kingdom touched the Bay of Bengal in the east and the Arabian Sea in the west. Gawan was one of the first ministers in Medieval India to order a systematic measurement of land, fixing the boundaries of villages and towns and making a thorough inquiry into the assessment of revenue in order to impose huge tributes to be paid by the . The King annexed Kanchi on 1st Muharram, 886 AH. This was the southernmost point ever reached by Bahmani.

British rule in Thondaimandalam

In 1763, the British East India Company assumed indirect control from the Nawab of the Carnatic over the Thondaimandalam region. The Company brought the territory under their direct control during the Second Anglo-Mysore War, and the Collectorate of Chingleput was created in 1794. The district was split into two in 1997 and Kanchipuram made the capital of the newly created Kanchipuram district.